Teeth can tell the tale: Norwegian forensic expert highlights crucial role of dental science in crime investigation

Dental evidence remains one of the most reliable ways to identify victims of crime and disaster when other biological markers fail, said Dr Sigrid Kvaal, a noted Norwegian forensic odontologist, during an interaction at NFSU conference in Gandhinagar on Saturday.

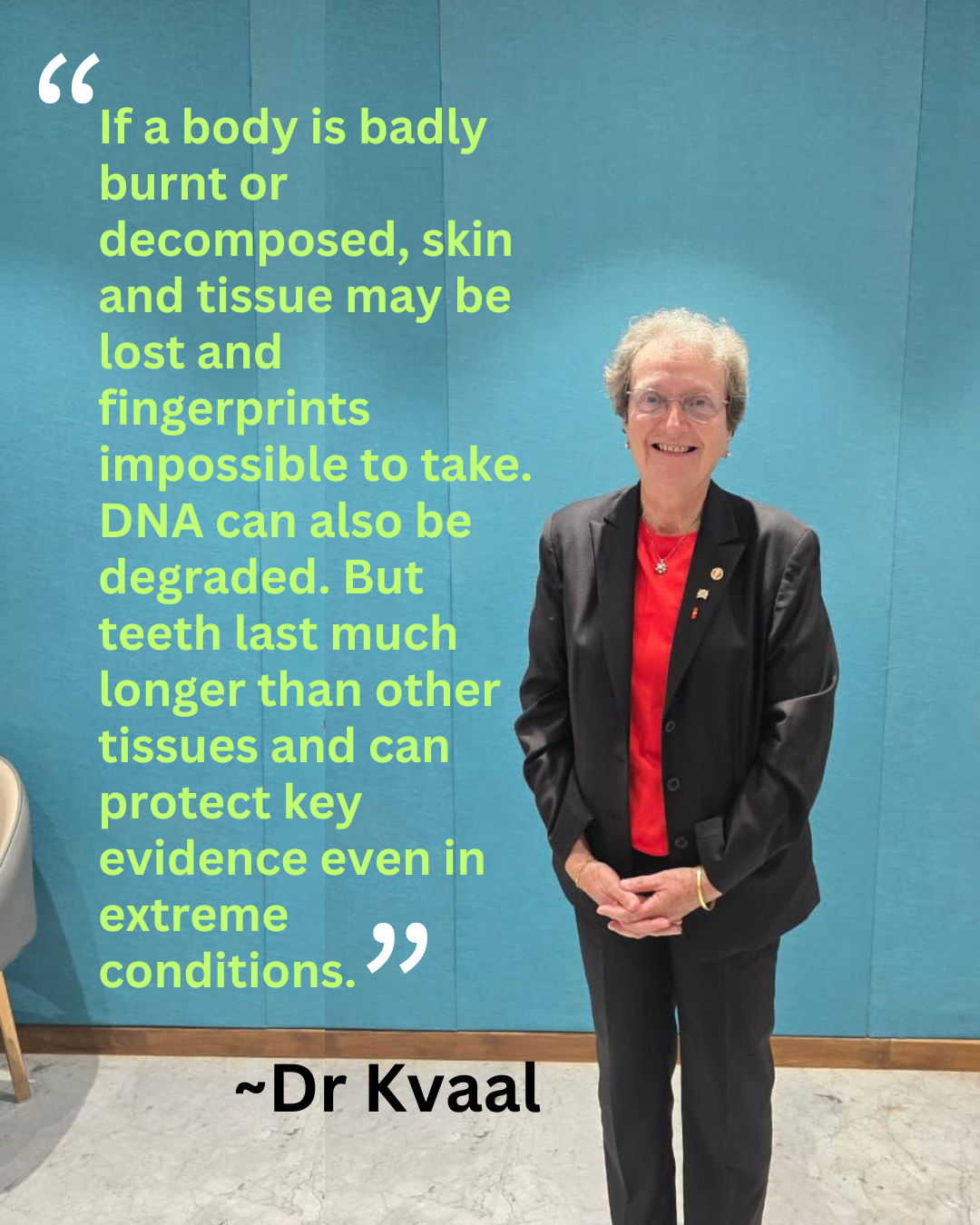

Dr Kvaal, who has taught forensic odontology for years and advised international police agencies, explained that teeth often survive conditions that destroy fingerprints or make DNA retrieval difficult. “If a body is badly burnt or decomposed, skin and tissue may be lost and fingerprints impossible to take. DNA can also be degraded. But teeth last much longer than other tissues and can protect key evidence even in extreme conditions,” she said.

Teeth as primary identifiers

The expert, who has worked closely with Interpol, said that the organisation recognises three primary identifiers for human remains—fingerprints, DNA and dental records. “Alongside these, medical implants, scars or tattoos can assist, but dental evidence is often decisive, particularly in cases of fire or when bodies are recovered long after death,” she said.

She recalled her experience of the 2011 Norway terror attack, where several young victims were found carrying multiple identity cards in the chaos. “In such situations, only dental records and DNA can conclusively confirm a person’s identity,” she added.

Establishing age and sex

Dental examination is also critical when official documents are missing. “We can estimate a person’s age and, to some extent, sex, which is vital for missing-person cases or when someone has no birth record,” Dr Kvaal explained. She cited recent cases where Norwegian police identified people who had disappeared in the year 1952, earlier using archived dental records.

Advances in imaging

Recent research, she said, is exploring MRI-based age estimation, avoiding the need for X-rays in living subjects where there is no medical reason for exposure. “MRI allows us to count pixels in images of developing teeth and reduces subjectivity compared with older X-ray methods,” she said.

Need for national dental record centres

Dr Kvaal urged Indian authorities to consider establishing a national dental records centre, which would help police and forensic teams quickly access dental histories without relying on individual dentists or families. “It would improve identification in disasters and also help clinicians avoid dangerous drug interactions during treatment,” she said.

Building international cooperation

Speaking about her long association with Indian universities, Dr Kvaal said she has been invited repeatedly to teach courses in forensic odontology. While no formal memorandum of understanding is planned with her Norwegian institution, she expressed hope that Indian dental colleges and child-protection departments will strengthen ties in areas such as the investigation of child abuse.